The Big Business of Therapy

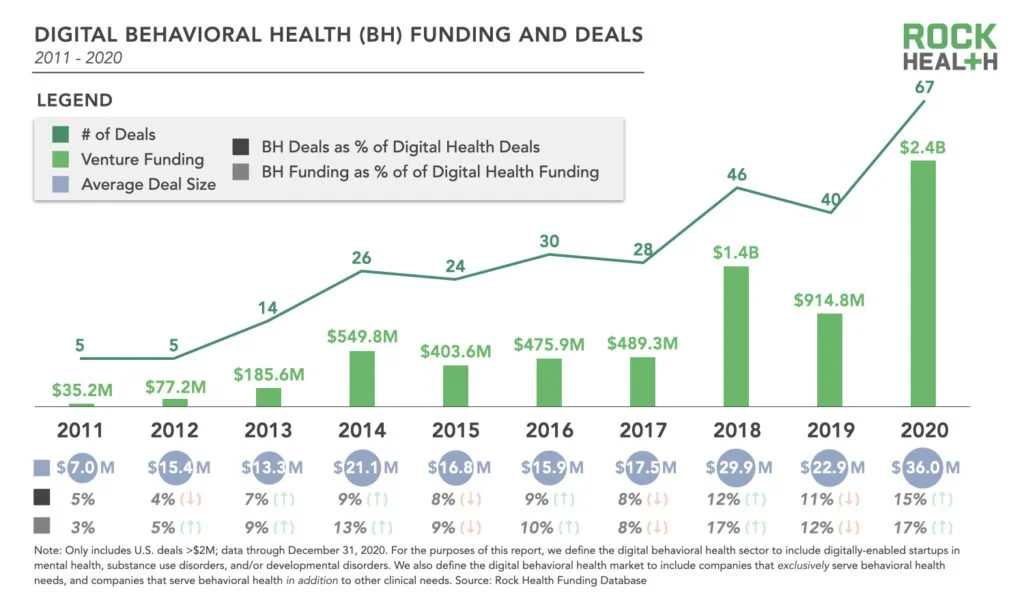

In recent years, a wave of venture capital and private equity firms have invested in the mental health field. On the surface, more investment in mental healthcare seems positive. After all, one in five American adults are managing a mental health issue, and both the public and private sectors have failed to meet the need for care.

At the same time, it is concerning that private equity and venture capital firms, which invest in businesses with the explicit goal of returning higher profits to shareholders, see an opportunity for growth within an industry whose primary goal is purportedly to treat mental health issues effectively.

While investors are driven by an increase in demand for mental health services, they are also attracted to the mental health industry because it can be a profitable and sticky business model. But, in my opinion, the mental health epidemic is a problem that needs to be solved, not exploited for financial gain.

Much has already been said and written about profiteering at addiction treatment chains and private psychiatric facilities, but the discourse has largely neglected similar, albeit more subtle, ethical dilemmas within mainstream psychotherapy.

Generally, the issue throughout private mental health care is rooted in the fundamental conflict of interest that arises when pursuing profit and providing people with the most effective treatment are misaligned.

Within psychotherapy, specifically, the overwhelming unmet demand for services has given profit-motivated entrepreneurs and investors the latitude to exploit the business model and even change the therapeutic process to fit their motivations. Although many of these companies are interested in providing high-quality services, I believe it is impossible to effectively treat mental health issues when the primary motivation is returning higher profits to investors.

Right now, if you search for therapy on the internet (or open any social media app), you’ll likely encounter advertisements for large private practice networks and virtual therapy tech companies. While individual sessions with these companies are technically “cheaper,” their business models are designed to sell ongoing, indefinite treatment for every client, which creates long-term profit.

For example, my colleague, who is a therapist at a private equity-owned network in New Jersey, earns additional financial incentives based on the number of sessions he can book, regardless of the quality or progress of the treatment itself.

Meanwhile, venture-capital backed start-ups like Cerebral and Talkspace are selling monthly subscriptions for “on-demand” virtual psychotherapy via text, video or call with unlimited therapist changes (tip: if you are looking for a discount at check-out, you can sign up for a long-term contract).

Finally, self-proclaimed futurist and hacker, Julian Sarokin, and serial tech entrepreneur, Herbert Bay, are competing to build “free” artificial intelligence therapists that you can message anytime from your phone.

By designing business models for profit growth, these companies are degrading the quality of therapy, depersonalizing the therapeutic relationship, and normalizing ongoing, indefinite therapy.

Speaking from my own experience, I got my first job as a therapist at a tech startup that uses an algorithm to match clients with therapists who fit their desired criteria. During our orientation week, the marketing director trained my cohort of first-year therapists on strategies to attract, acquire and retain clients using their own user-generated data.

To attract new clients, he suggested that we list “specializations” on our profiles, regardless of our training, that matched their clients’ most commonly reported conditions and preferred therapy techniques. And to increase our chances of retaining long-term clients, the marketing director encouraged us to set up recurring calendar appointments with clients and deny requests for semi-regular appointments, which normalized ongoing, weekly therapy for everyone.

At this company, therapists were salespeople pursuing subscribers to an app rather than licensed clinicians helping people find the best care for their specific needs. Personally, I felt a great deal of pressure there to maintain recurring clients, and it affected my clinical approach. On numerous occasions, I was reluctant to confront or challenge a client if I felt they might stop meeting with me because I needed to maintain a high volume of sessions. Ultimately, the company’s similarity to a run-of-the-mill tech start-up was laid bare when they fired over half of my cohort within three months because the company had expanded too quickly.

It’s no secret that private therapists are financially incentivized to provide long-term, ongoing treatment to every client. And while long-term psychotherapy is necessary for some folks and could be beneficial for anyone, it is by no means the only option, nor is it the most effective treatment for everyone. For some clients, shorter-term options, like problem-solving therapy or eight-week DBT programs are more appropriate and cost-effective.

By selling psychotherapy as a subscription service, companies like BetterHelp undermine the scientific discipline of individualized psychotherapy and render the services inaccessible for those who can only afford flexible or short-term treatment.

Finally, while it seems reasonable for mental health companies to adjust their services to reach more clients with features like “on-demand” messaging and unlimited therapist changes, they also risk the privacy of clients’ confidential information and devalue the importance of creating strong therapeutic relationships, which is the cornerstone of the healing process.

Moving forward, I believe the industry needs to encourage non-profit business models with salaried positions for therapists to limit the natural conflict of interest that arises when profit growth is the priority. In the meantime, it is up to my peers and our clients to hold the industry accountable.

So, if you are currently looking for a therapist, it is important that you research the company’s owners and investors. Once you feel comfortable with the company’s financial motivations and have identified a therapist, you should discuss the financial structure, therapeutic approach and duration of treatment with your therapist. In turn, the therapist will likely advise a course of treatment that addresses your specific needs and develop checkpoints throughout treatment to ensure your needs are being met. This is not a perfect solution to the underlying problem, but it puts more power back in the clients’ hands where it belongs.